When I signed up Bob Dylan to be in a book about folk singers in the early 1960’s, hardly anyone had ever heard of him. Bob would come into my office with his scruffy little newsboy cap and chubby cheeks, sit down at the typewriter and start pounding those keys, verse after verse, hammering out songs such as Masters of War, Song to Woody and other memorable new works. Then we’d go over to the little recording studio up at Columbia Records and he’d play it through just once with his guitar and harmonica. Finally we’d take the tape down to Earl Robinson for transcription into playable chords and tablature. It was amazing how quickly he worked, and how sure he was of what he was doing.

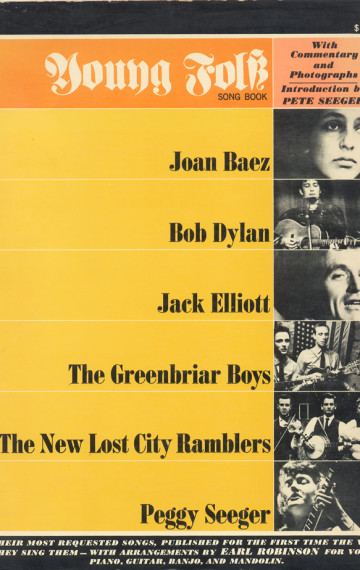

Bob was one of several folk artists of that period we put into the book, which included songs, tablature, photographs and musical exegesis about Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, the Greenbriar Boys and others. A lot of my pundit advisors of that period were opposed to putting him in the book since he was so young and unproven, and too much of a beginner for the purists and folk aficionados. Many of the traditional folk labels and critics didn’t take him seriously and frankly rejected him wholesale at that time.

Meanwhile Dylan was soaking up everything around him. As his advocate and friend during his first experience dealing with fame and recognition, I tried to help him pick songs for the book, and edit them (since most of them were way long, rough, and always changing), and to place them in our context of text and photographs. He was also always ready for a free meal during those years and a game of penny nickel poker. One night I played him an old Billie Holiday recording. He had never heard of her.

Dylan’s memoir Chronicles documents those years very well, and could have been entitled The Very Rapid Education of Robert Zimmerman.