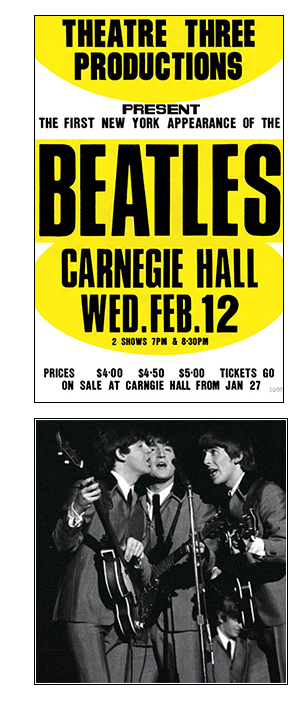

I sure have. It was 1964 and I was on assignment for The Nation magazine to write a review of the Beatles at Carnegie Hall, their first live appearance in the United States.

I sure have. It was 1964 and I was on assignment for The Nation magazine to write a review of the Beatles at Carnegie Hall, their first live appearance in the United States.

No Soul in Beatlesville

There I was, standing on a shaky balcony seat trying to see the stage over a mob of hysterical, screaming and sobbing 13-year-old girls. I was 25 years old and a rhythm and blues purist, a wannabee soul brother. I didn’t get the Beatles.

My review? It was vicious. I called it No Soul in Beatlesville and eviscerated the band as “derivative, a deliberate imitation…manna for dull minds”.

I’ve been apologizing ever since.

“Ok,” I later told my musical family and friends, “I was an idiot. I admit it!”

I should have counted to ten, reconsidered what I’d written more carefully, sought an outside opinion. (My mantra as a developmental editor.) But I didn’t, and The Nation published it as written. It’s been coming back to haunt me ever since. Fifty years of mortifying shame. Oy vey!

It’s back to bite me yet again

Will it ever stop? Now, to throw some salt on it, The Nation is marking the 50th anniversary of the Beatles arrival on these shores in their upcoming issue by reprinting my embarrassing review as a “Blast from the Past” with commentary by Editor and Publisher Katherine vanden Heuvel.

Here’s what she writes about my original essay:

“If we are told to remember the Beatles’ arrival in the United States fifty years ago last month as an “invasion,” it is as one that was unopposed. The 73 million people who watched [on the Ed Sullivan show] Paul McCartney count the band into “All My Loving” on February 9, 1964 shattered all records, representing nearly two-fifths of the US population at the time, despite the fact that only 17 percent of American homes even had televisions in them. We surrendered without resistance, it often seems-a view evident in one Amazon review of a collection of the late Bill Eppridge’s photographs from the Beatles’ first week in the US. “Those six days did change the world,” the commenter writes, “by simply unifying us all with faces of sheer happiness.”

At least one person wasn’t smiling. In an essay published in our March 3, 1964 issue, a young Simon & Schuster editor named Alan Rinzler objected to the furor over the Liverpool lads’ music and-correctly, if somewhat myopically-attributed Beatlemania to a massive, premeditated PR campaign. The quivering throngs of teen-aged girls, he believed, said much more about the susceptibility of Americans to fashionable trends than it did about the talent or novelty of the group itself.”

An excerpt from the review:

“By the time the Beatles actually appeared on the stage at Carnegie Hall, there wasn’t a person in the house who didn’t know exactly what to do: flip, wig-out, flake, swan, fall, get zonked-or at least try.

The Beatles themselves were impressive in their detachment. They came to America “for the money.” They attribute their success “to our press agent.” They looked down at their screaming, undulating audience with what appeared to be considerable amusement and no small understanding of what their slightest twitch or toss of the head could produce.

John Lennon, the leader of the group, seemed particularly contemptuous, mocking the audience several times during the evening, and openly ridiculing a young girl in the first row who tried to claw her way convulsively to the stage. Paul McCartney bobbed his head sweetly, his composure broken only when-horror of horrors-his guitar came unplugged. (There was a terrible moment of silence. One expected him to run down altogether, and dissolve into a pool of quivering static.) George Harrison tuned his guitar continually and seemed preoccupied with someone or something at stage right. Ringo Starr, the drummer, seemed the only authentic wild man of the group, totally engrossed in his own private cacophony. For the rest, it was just another one-night stand.

This is probably why the reaction at Carnegie Hall wasn’t a real response to a real stimulus. There weren’t too many soul people there that night either on the stage or in the audience. The full house was made up largely of upper-middle-class young ladies, stylishly dressed, carefully made up, brought into town by private cars or suburban buses for their night to howl, to let go, scream, bump, twist, and clutch themselves ecstatically out there in the floodlights for everyone to see; and with the full blessings of indulgent parents, profiteering businessmen, gleeful national media, even the police. This was their chance to attempt a very safe and private kind of rapture.

Most did what was expected of them and went home disappointed. Disappointed because nothing really passed from the stage to the audience that night, nor from one member of the audience to another unless some of them went on to Find a fuck buddy to make up for what a disappointment the show was. There was mayhem and clapping of hands, but none of the exultation, no sense of a shared experience.

Ouch!

There’s practically nothing in this snooty piece that I agree with now. The songs they performed that night at Carnegie Hall – “Please please me”, “I saw her standing there”, “Love me do”, “I want to hold your hand” — were all quite excellent, but I couldn’t actually hear them over the of the audience bedlam. I didn’t become a big fan until the following year with the 1965 release of the superb album Rubber Soul, followed shortly by the equally terrific Revolver in 1966.

Meanwhile, my day job was at Simon & Schuster, where I was involved with the publication of Yoko Ono’s avant-garde book Grapefruit and John Lennon’s A Spaniard in the Works, though neither of them actually knew the other at that time.

Then, in 1968, my musical and publishing interests led me to become one of the pioneering staff members of Rolling Stone Magazine. I opened the first New York office then moved to the original home office in San Francisco, where I was the Associate Publisher and Vice-President, as well as editor-in-chief of the books division Straight Arrow.

In that capacity I published several books on the Beatles and was a huge fan, a major promulgator of editorial work on their personal and professional lives. Later, when Lennon was assassinated, I was at Bantam Books, responsible for publishing the memorial book Strawberry Fields Forever.

Nevertheless that old Nation review comes back to skewer me every once in a while. Even my own adult children can’t believe I wrote it, but I think they’ve forgiven me. Hope you will, too.

Meanwhile, don’t be afraid to reconsider or change your mind about something you wrote before sending it out into the cold, cruel world. You may have to live with its unintended consequences for the rest of your life.

How to avoid embarrassment

These days, I always urge authors to follow these guidelines:

• Never settle for your first draft no matter how good you think it is

• Get a second opinion from a professional, objective editor

• Be willing to rewrite, check again, rewrite, for as many times as it takes.

What about you?

Have you ever written or published something you wish you could take back? Come on, you can tell us.

Takes a great person to write a blog on their own mistakes! I think most all have articles they have written that they either want back if it is done for someone else when published or that they will go back and edit on their own site. I try and let drafts sit for a couple of days. I find it turns out much better when I do it that way.

The other issue I have is something gets published and then the situation changes that I worry that I am giving non current information. I can edit it on my site but if it is being published somewhere else then there is a real concern of not misleading someone that is reading something 2 years old.

I pitched a concept to Wingspan Quarterly and in 2006 embarked on an aggressive investigation resulting in publication of a fictional work, “I Found God in Cyberspace.” The story was about the experiences of an aspiring novelist facing a Big House marketplace and the issue of free speech on the internet. My original intent was to achieve a little name recognition for my first novel, Rarity from the Hollow. At that time, the SF/F Writer’s Association had member email addresses on its site. I wrote everybody. I registered and posted debate on forums, a couple of which I’m still banned for life. A popular blog insulted me publicly (Scalzi, after all it was his “property”). In summary, I pissed off everybody who might have been helpful in promotion of my novel (but, probably not given egocentrism and profit-motive). Today, one reaction from a moderator can still pop up on Google, “some people on the internet just don’t get it….” I kind of regret writing that story, but it was sooooooooooo good. On the other hand, the mag. went defunct and is now only available on Barnes and N if one looks really hard.

I agree with Anne above but also in awe at how deft young Alan’s writing was. As for regretting published work – yes. I was 20-years-old when I wrote a brief behind-the-scenes article of a highly visible administrator resigning over the public usage of a racial slur. I was, unknowingly, a political pawn that got played. My idealistic attempt for justice was misguided. http://www.newsreview.com/sacramento/before-the-slur/content?oid=4777

Also, I am taking a magazine writing course now – to exercise those muscles – and I am bored to tears. I regret the money spent on that class and can predict I will regret writing whatever I end up submitting to the San Diego City magazine.

Great Read and Story! Thanks for the humanization.

It’s not that I write, or what I write. But that I write whatever it is and, though satisfied, feel that someting is amiss. Something that very well could have been remedied by a second opinion.

Normally not the person to react. But couldn’t help myeself just now.

Who says, simply because they became superstars, that you weren’t spot on about the performance that night?

And about the audiance for that matter?

Sure you can change your opinion, but it was true at that moment in your experience. Never be sorry for that!

I thought it was OK. You commented on the experience, not the music. And it felt like an accurate depiction. I was one of 2 or 3 males in the audience when I saw the Beatles in Chicago September (?) 1964. I remember the excitement and screaming but I don’t think that I heard a note of the music.

Yes, my site’s most popular blog article. Maybe I don’t regret writing it so much as the reaction. Still, with a blog post you control it, right? You can delete it anytime. Well, yeah, but who knows who may have saved that post somewhere to throw out at you when you’re least expecting it?

And oftentimes that thing we may regret we may secretly like too. Perhaps it’s the only thing bringing us attention. That can also be incredibly sad as well.

Anne,

Thanks for the kind words. You’re right, who knew then what megastars they’d become. But in retrospect the Beatles were an extraordinary band and for a brief, shining period (I’d say 1965 to 1970) they went way beyond being being ordinary bestselling recording and performing superstars like the Rolling Stones or the Beach Boys. Without consciously trying, their words and lyrics seemed to represent our deepest collective feelings in the sixties, from hope to disappointment, inspiration to despair, until, as Lennon said in 1970 “The dream is over”.

The songs they wrote (including Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison, too) are still wonderful but I think more meaningful to those who came of age in the sixties, the aging baby boomers, than for younger folks today.

I’m glad to have seen them from their first performance and been swept up in the collective dream.

I don’t think the review was all that bad. You took your personal experience from that night and put it on the page. You found each of the band members nuances. John’s looking off stage. Paul’s embarrassment over his unplugged guitar, Ringo being Ringo. And I have to agree. When they first came to the US they were only looking to make money. Who knew they would be become megastars? Don’t beat yourself up. I wouldn’t. I rather liked the review.

Don’t feel badly. Whenever I think of things I wished I hadn’t said, all always remember this quote from my father circa 1956.

“Huh. Six months from now, no one will even remember who Elvin Pressler is.”